I was reading articles about TDD and I found the following one. https://blog.cleancoder.com/uncle-bob/2017/03/03/TDD-Harms-Architecture.html

In order to answer this question I think someone should read the full article, but in any case I'll quote the part I'm not able to grasp or to picture in my head.

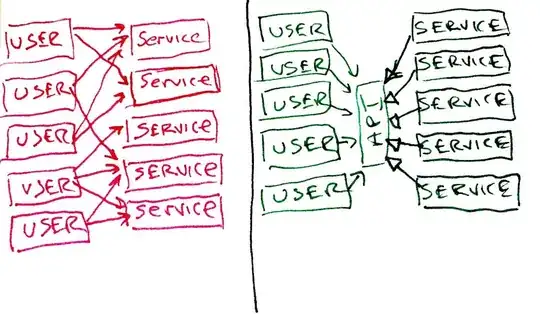

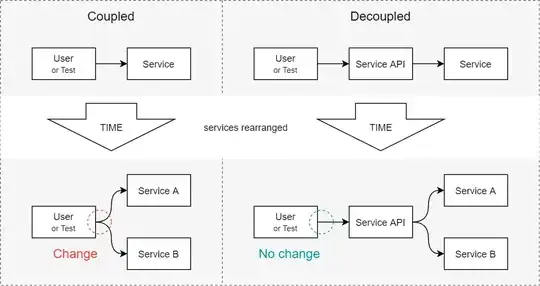

The right side [...] decouples the users from the services by using an API. What’s more, the services implement the API using inheritance, or some other form of polymorphism [...]

...Okay I guess

I want you to make a simple substitution. Look at that diagram, and substitute the word “TEST” for the word “USER” – and then think. Yes. That’s right. Tests need to be designed. Principles of design apply to tests just as much as they apply to regular code. Tests are part of the system; and they must be maintained to the same standards as any other part of the system.

Here is the part I don't understand. I just don't see an API reducing all those dependencies, for me an API just provides endpoints to be called from outside the application... How come that all that coupling is going to automatically dissapear if I change my backend to be connected within an API?

I'm just too blind to see how it would work... I'd love to understand it because I've been using TDD for two years now and I have suffered that pain he talks about whenever I need to refactor my tests just because we perform a clean up in the backend.

Can anybody come up with a snippet showing how it would work or which concept should I focus on to understand it better?