Anecdotally

I am a consultant developer. I have been hired on several occasions specifically to "fix the development issues". Some customers are aware of issues in their development process, whereas others only see it as a bunch of bugs that need to be fixed without looking at the cause of the bugs (i.e. bad coding practices).

In my experience, one company that asked for help in fixing the development process was actually interested in taking steps to improve the development process. In other companies, their interest existed up until it required action from their side (e.g. reprimanding a developer who actively rolls back refactoring or improvements, or actually giving me access to the tools needed to set up a CI/CD pipeline).

Based on my experience, bad practice starts off as a developer deficiency. Not a willful one, but rather a matter of either inexperience or general corner-cutting attitude. Whatever the cause, these developers will show quick results due to not taking the time for due diligence such as testing, reviewing or refactoring.

Management will notice those quick results, and will over time come to expect this efficiency. They don't handle the fallout from bad practice (i.e. bugs) directly, but they do benefit from the shorter development times.

At this point, it becomes a feedback loop. Management communicates expected (quick) deadline. Developers are forced to cut corners to achieve it. The codebase degrades. The initial quick release turns into a maintenance cycle of unclear and erratic bugs, regressions, and general lack of readability. In order to cope, while keeping up with the continuing demand for quick results, developers are forced to cut corners in their bugfixes.

The cycle continues, while the quality and performance of the codebase is eroded, and also the good practice skills of developers erode and start being regarded as "needlessly" time consuming. If some developers stick to good practice and others don't, management will judge them based on how quickly they deliver - without observing the bugs or the causes of the bugs.

The good practice developers are deincentivized, the bad practice developers are incentivized. Over time, due to positive/negative feedback from management, the bad practice developers take on a more leading role than the good practice developers, and the bad practice becomes the law of the land.

Speaking from the experience of a company whose main workforce was external consultants, the good practice devs simply leave or become disenfranchised bad practice devs. The (initial) bad practice devs stick around. This perpetuates the imbalance of the bad practice devs having seniority over the good practice devs.

At this point, bad practice has become an endemic company culture. It is reinforced from all sides (including the sales department in case of dev companies), and any good practice suggestion that pops up is often drowned out by the popular support for bad practice, combined with management's intolerance for longer deadlines.

This devolution is something I've observed with at least three different companies. The same events and general work climate pervaded through all three companies.

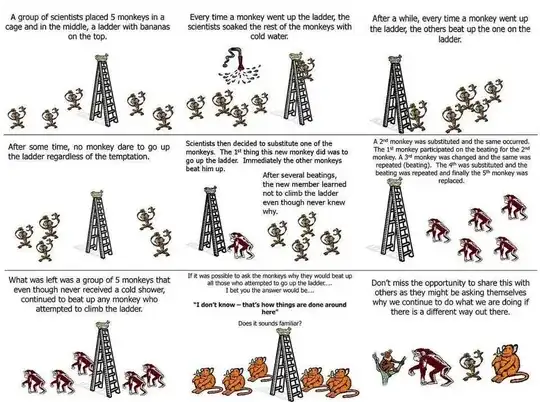

The monkeys and the ladder

Whenever I talk about detrimental company culture, which often manifests as a "this is how we've always done it" attitude, I am reminded of the parable of the monkeys and the ladder.

Suppose I had turned off the shower around the time of picture 4. The monkeys could have gone up that ladder without any repercussions, but their "company culture" prevented it from happening, based on what is now an outdated idea (since the shower is no longer active).

This parable touches exactly on the erosion of good practice that takes place. Popular but misguided support for bad practice inhibits anyone who tries to make a change for the better by introducing good practice.

The issue isn't with social checks and balances. The same principle is used in other companies to keep up the good practice and squash any bad practice suggestions.

The issue is with the blind acceptance of "things are done this way" without ever being able to re-evaluate. When it reaches that stage, the behavior is a company culture.

Answering your questions

Generally, is tech debt issue an org culture issue or just lack of tool/insight?

It depends what stage of the process you are on. In the beginning, it's a lack of insight and/or tooling. But when combined with management that looks only at results and not ongoing issues and thus wrongly (possibly unknowingly) incentivizes the bad practice, it becomes a feedback loop and over time turns into company culture.