I have come to suspect that well-written code can follow OO principles and functional principles at the same time. I'm trying to reconcile these ideas and the big sticking point that I've landed on is return.

I've been trying my best to reconcile some of the benefits of, more specifically, imperative and functional programming (naturally not getting all the benefits whatsoever, but trying to get the lion's share of both), though return is actually fundamental to doing that in a straightforward fashion for me in many cases.

With respect to trying to avoid return statements outright, I tried to mull over this for the past hour or so and basically stack overflowed my brain a number of times. I can see the appeal of it in terms of enforcing the strongest level of encapsulation and information hiding in favor of very autonomous objects that are merely told what to do, and I do like exploring the extremities of ideas if only to try to get a better understanding of how they work.

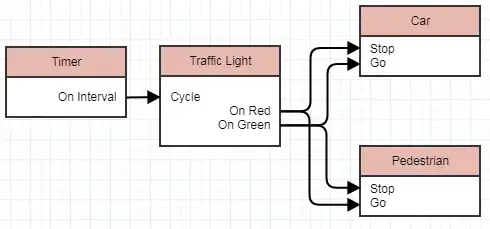

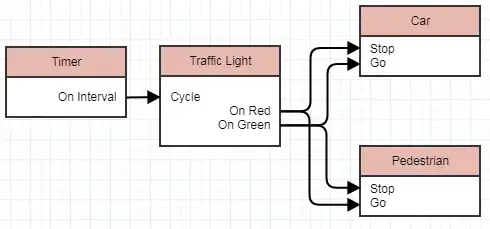

If we use the traffic light example, then immediately a naive attempt would want to give such traffic light knowledge of the entire world that surrounds it, and that would certainly be undesirable from a coupling perspective. So if I understand correctly you abstract that away and decouple in favor of generalizing the concept of I/O ports which further propagate messages and requests, not data, through the pipeline, and basically inject these objects with the desired interactions/requests among each other while oblivious to each other.

The Nodal Pipeline

And that diagram is about as far as I got trying to sketch this out (and while simple, I had to keep changing it and rethinking it). Immediately I tend to think a design with this level of decoupling and abstraction would find its way becoming very difficult to reason about in code form, because the orchestrator(s) who wire all these things up for a complex world might find it very difficult to keep track of all these interactions and requests in order to create the desired pipeline. In visual form, however, it might be reasonably straightforward to just draw these things out as a graph and link everything up and see things happening interactively.

In terms of side effects, I could see this being free of "side effects" in the sense that these requests could, on the call stack, lead to a chain of commands for each thread to perform, e.g. (I don't count this as a "side effect" in a pragmatic sense as it is not altering any state relevant to the outside world until such commands are actually executed -- the practical goal to me in most software is not to eliminate side effects but defer and centralize them). And furthermore the command execution might output a new world as opposed to mutating the existing one. My brain is really taxed just trying to comprehend all this however, absent any attempt at prototyping these ideas. I also didn't try to tackle how to pass parameters along with the requests in favor of just trying a timid approach at first of thinking of all of these requests as nullary functions with a uniform signature/interface.

How it Works

So to clarify I was imagining how you actually program this. The way I was seeing it working was actually the diagram above capturing the user-end (programmer's) workflow. You can drag a traffic light into the world, drag a timer, give it an elapsed period (upon "constructing" it). The timer has an On Interval event (output port), you can connect that to the traffic light so that on such events, it's telling the light to cycle through its colors.

The traffic light might then, on switching to certain colors, emit outputs (events) like, On Red, at which point we might drag a pedestrian into our world and make that event tell the pedestrian to start walking... or we might drag birds into our scene and make it so when the light turns red, we tell birds to start flying and flapping their wings... or maybe when the light turns red, we tell a bomb to explode -- whatever we want, and with the objects being completely oblivious to each other, and doing nothing but indirectly telling each other what to do through this abstract input/output concept.

And they fully encapsulate their state and reveal nothing about it (unless these "events" are considered TMI, at which point I'd have to rethink things a lot), they tell each other things to do indirectly, they don't ask. And they're uber decoupled. Nothing knows about anything except this generalized input/output port abstraction.

Practical Use Cases?

I could see this type of thing being useful as a high-level domain-specific embedded language in certain domains to orchestrate all these autonomous objects which know nothing about the surrounding world, expose nothing of their internal state post construction, and basically just propagate requests among each other which we can change and tweak to our hearts' content. At the moment I feel like this is very domain-specific, or maybe I just haven't put enough thought into it, because it's very difficult for me to wrap my brain around with the types of things I regularly develop (I often work with rather low-mid-level code) if I were to interpret Tell, Don't Ask to such extremities and want the strongest level of encapsulation imaginable. But if we're working with high-level abstractions in a specific domain, this might be a very useful way to program it and express how things interact with each other in a rather uniform fashion that doesn't get muddled up in the state, or computations/outputs, of its objects, with uber decoupling of a kind where even the analogical caller need not not know much, if anything, about its callee, or vice versa.

Signals and Slots

This design looked oddly familiar to me until I realized it's basically signals and slots if we don't take a lot the nuances of how it's implemented into account. The main question to me is how effectively we can program these individual nodes (objects) in the graph as strictly adhering to Tell, Don't Ask, taken to the degree of avoiding return statements, and whether we can evaluate said graph without mutations (in parallel, e.g., absent locking). That's where the magical benefits are is not in how we wire these things together potentially, but how they can be implemented to this degree of encapsulation absent mutations. Both of these seem feasible to me, but I'm not sure how widely applicable it would be, and that's where I'm a bit stumped trying to work through potential use cases.