Acceptance tests act at a very different level than, say, unit tests.

A unit test is very precise: it deals with one method, sometimes a part of a method. This makes it a perfect choice for regression testing. You make a change. A test fails while it passed during the previous commit. Great, you can easily pinpoint the source of the regression both in time (from commit N-1 to commit N) and space (this method of this class).

With acceptance tests, good luck if some start to fail. One bad change may cause one acceptance test to fail, or maybe ten tests, or a hundred. When you look at those hundred tests turning red without giving any hint about the location of the bug, the only thing which comes to mind is to revert to previous commit and start over.

Imagine acceptance tests as tests which consider the system as a black-box and which test a feature of the system. The feature may involve thousands of methods to be run, may rely on a database, a message queue service, a few dozen of other things. An acceptance test doesn't care how much stuff is being involved, and don't all the magic which happens behind the scenes. This also means that multiple acceptance tests may rely on the same method, which in turn means that a regression in a single method often leads to several failed acceptance tests. I had cases where a regression caused suddenly approximately fifty system and acceptance tests to fail, without giving any hint about the location of the bug.

Unit tests consider the system as a white-box. They are aware of the concrete implementations, and test a specific method, not a feature. By using mocks and stubs, unit tests achieve enough isolation to not being affected by the world: if the method works, the tests succeed. If the method has a regression, those tests fail. If another method somewhere in the code base doesn't work, those unit tests still pass.

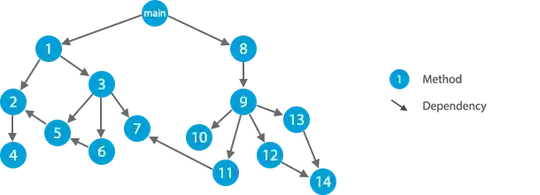

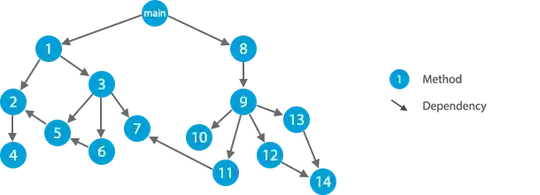

Imagine the following diagram which represents methods calling other methods:

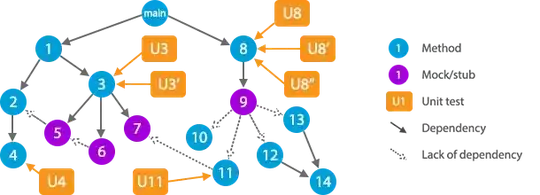

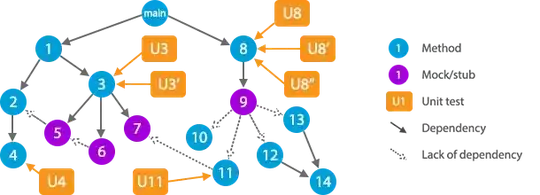

Unit testing can be represented this way:

For example, unit tests U3 and U3′ are not affected by bugs in method 6, because it is replaced by a stub. Nor is it affected by the regressions in method 2, because the stub 5 doesn't rely on method 2. In the same way, U8″ doesn't care about method 7, because 9 is a stub and doesn't rely on 11 which in turn uses 7.

Imagine you make a commit and your CI informs you that U8′ now fails. Where would you search for the problem?

In U8′. Maybe the code it tests is correct, but the test is not. This happens, for instance, when requirements change: you change the code but forget to reflect the change in the tests.

In method 8. There could be a regression.

In stub 9. Maybe you implemented a change in code and in tests, but forgot to change the stubs.

On the other hand, you are sure the problem is not with method 11 or method 7.

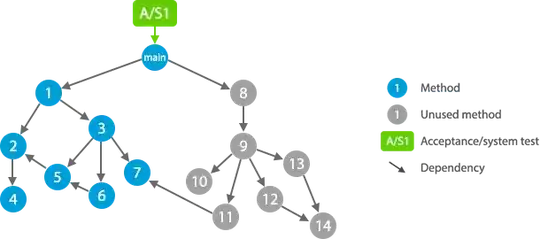

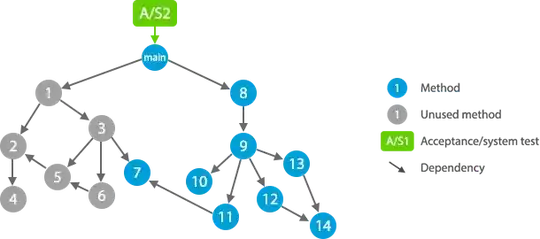

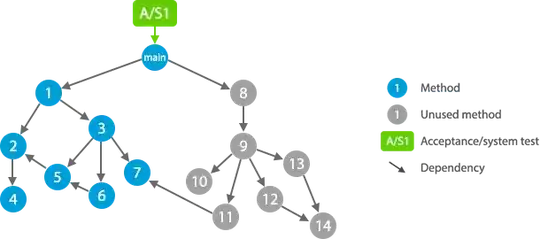

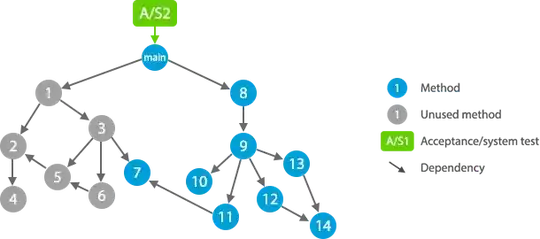

Now this is how acceptance or system tests would look like:

Imagine you make a commit and your CI informs you that A/S2 failed. Guess where is the problem? Much more difficult, isn't it.

Obviously, another aspect is that, as I described above, a small change can cause many acceptance tests to fail. For instance, a regression in method 7 may lead to A/S1 and A/S2 to fail. With unit tests, a regression in method 11 may cause U11 to fail, but will not affect, for instance, U8.

This leads to a huge benefit: the time you spend locating regressions. I've seen programmers who, when a regression is found, simply revert the source to the latest working commit and start over, because the code is a mess, and they don't enjoy spending hours debugging, hoping to find the origin of the problem. This is unfortunate, especially when commits are done not as frequently as they can be.

With unit tests, you don't waste all this time. They simply tell you that you have an issue with a given method in a given class, so you can focus your attention to the concerned method right after you discover the regression.

- Unit tests ensure things at a lower level are correct: Who cares? if the business is happy with what they've received, then what difference does it make? [...]

Have you worked with really bad projects where you can't make a change without breaking at least ten things in random locations?

Unit tests don't magically solve this problem. However, you should care that things are correct at lower level. Quick hacks have a substantial maintenance costs. On the other hand, if the only thing programmers have are acceptance tests (and tight deadlines; and no insensitive to do their job correctly), when an acceptance test fails because somewhere, the font should be 12px, but appears to be 10px, they may eventually just end up writing:

this.font = 12;

and wait until testers get back to them telling that now, the font is 12px in situations where it should be 14px.

- Unit tests speed up long-term development time: Is it really worth the trade-off? Where there is code there are bugs, tests are not exempt from this. [...]

Tests won't magically make bugs go away. However, practice shows that writing a test, checking that it fails, then implementing the feature and checking that the test passes appeared to be a practice which generally leads to less bugs.

Similarly, why would anyone do code reviews? Reviewers are not exempt from lack of attention, and there are plenty of cases where a bug is missed by several reviewers and maintainers. This being said, you get more bugs without code reviews than with them.

Is it worth it? For your personal small app, not really. For business-critical code, yes, indeed.

- Unit tests ensure good architecture: No they don't. [...]

They do, somehow. By forcing to test methods in isolation, you force programmers to rethink coupling. Unit testing usually leads to short methods, classes which do one and one only thing (Single responsibility principle), dependency injection, etc.

A 4000 LOC method which relies on a few hundred other methods and requires access to the database is impossible to unit test (while it is perfectly normal to add acceptance tests to such method).

In Going TDD in the middle of the project, I describe specifically this sort of projects. Bad architecture led to the case where it was practically impossible to add unit tests later. If unit tests were considered from the beginning, it would reduce the disaster. The code would still be bad (since written by the same programmers who were fine writing a 400 LOC spaghetti method), but not that bad.

- Integration tests ensure the overall performance is accurate and optimal [...]

Don't know. Never heard of that. Performance should be checked by tests corresponding to the performance non-functional requirements.

- Functional tests ensure that output is as expected [...]

Don't know.

- TDD ensures that when changes are implemented, nothing else breaks in the process: Acceptance tests will ensure this too since everything's based on business requirements/features. [...]

No, this is the role of regression testing. TDD's purpose is mainly to avoid writing tests which are not testing anything. This is why in TDD, the test should fail before you implement a feature: otherwise, either the test is wrong, or you actually don't need the feature.