A lot of people answered already. Thought I'd give my own personal perspective.

Once upon a time I worked on an app (and still do) that creates music.

The app had an abstract Scale class with several subclasses: CMajor, DMinor, etc. Scale looked something like so:

public abstract class Scale {

protected Note[] notes;

public Scale() {

loadNotes();

}

// .. some other stuff ommited

protected abstract void loadNotes(); /* subclasses put notes in the array

in this method. */

}

The music generators worked with a specific Scale instance to generate music. The user would select a scale from a list, to generate music from.

One day, a cool idea came to my mind: why not allow the user to create his/her own scales? The user would select notes from a list, press a button, and a new scale would be added to the list available scales.

But I wasn't able to do this. That was because all the scales are already set at compile time - since they are expressed as classes. Then it hit me:

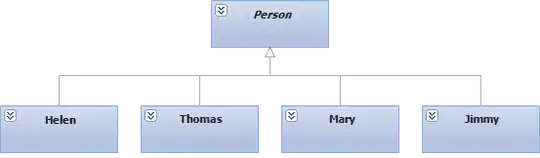

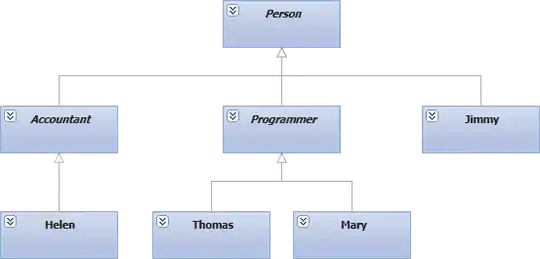

It's often intuitive to think in terms of 'superclasses and subclasses'. Almost everything can be expressed through this system: superclass Person and subclasses John and Mary; superclass Car and subclasses Volvo and Mazda; superclass Missile and subclasses SpeedRocked, LandMine and TrippleExplodingThingy.

It's very natural to think in this way, especially for the person relatively new to OO.

But we should always remember that classes are templates, and objects are content poured into these templates. You can pour whatever content you want into the template, creating countless possibilities.

It's not the job of the subclass to fill the template. It's the job of the object. The job of the subclass is to add actual functionality, or expand the template.

And that's why I should have created a concrete Scale class, with a Note[] field, and let objects fill in this template; possibly through the constructor or something. And eventually, so I did.

Every time you design a template in a class (e.g., an empty Note[] member that needs to be filled, or a String name field that needs to be assigned a value), remember that it's the job of the objects of this class to fill in the template (or possibly those creating these objects). Subclasses are meant to add functionality, not to fill in templates.

You might be tempted to create a "superclass Person, subclasses John and Mary" kind of system, like you did, because you like the formality this gets you.

This way, you can just say Person p = new Mary(), instead of Person p = new Person("Mary", 57, Sex.FEMALE). It makes things more organized, and more structured. But as we said, creating a new class for every combination of data isn't good approach, since it bloats the code for nothing and limits you in terms of runtime abilities.

So here's a solution: use a basic factory, might even be a static one. Like so:

public final class PersonFactory {

private PersonFactory() { }

public static Person createJohn(){

return new Person("John", 40, Sex.MALE);

}

public static Person createMary(){

return new Person("Mary", 57, Sex.FEMALE);

}

// ...

}

This way, you can easily use the 'presets' the 'come with the program', like so: Person mary = PersonFactory.createMary(), but you also reserve the right to design new persons dynamically, for example in the case that you want to allow the user to do so. E.g.:

// .. requesting the user for input ..

String name = // user input

int age = // user input

Sex sex = // user input, interpreted

Person newPerson = new Person(name, age, sex);

Or even better: do something like so:

public final class PersonFactory {

private PersonFactory() { }

private static Map<String, Person> persons = new HashMap<>();

private static Map<String, PersonData> personBlueprints = new HashMap<>();

public static void addPerson(Person person){

persons.put(person.getName(), person);

}

public static Person getPerson(String name){

return persons.get(name);

}

public static Person createPerson(String blueprintName){

PersonData data = personBlueprints.get(blueprintName);

return new Person(data.name, data.age, data.sex);

}

// .. or, alternative to the last method

public static Person createPerson(String personName){

Person blueprint = persons.get(personName);

return new Person(blueprint.getName(), blueprint.getAge(), blueprint.getSex());

}

}

public class PersonData {

public String name;

public int age;

public Sex sex;

public PersonData(String name, int age, Sex sex){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.sex = sex;

}

}

I got carried away. I think you get the idea.

Subclasses are not meant to fill in the templates set by their superclasses. Subclasses are meant to add functionality. Object are meant to fill in the templates, that's what they're for.

You shouldn't be creating a new class for every possible combination of data. (Just like I shouldn't have created a new Scale subclass for every possible combination of Notes).

Her'es a guideline: whenever you create a new subclass, consider if it adds any new functionality that doesn't exist in the superclass. If the answer to that question is "no", than you might be trying to 'fill in the template' of the superclass, in which case just create an object. (And possibly a Factory with 'presets', to make life easier).

Hope that helps.