Radio Frequency amplifiers quite often use common base circuits and I believe the main reason is because "miller capacitance" does not have the same detrimental effect.

On a normal common-emitter configuration, the input is fed to the base and the output is at the collector but, internally the capacitance between collector and base acts as negative feedback and can reduce gain.

To combat this, if the base is held at a fixed potential to ground (as per in its normally biased state), and this is supplemented by decent capacitance to ground, the miller capacitance is effectively shunted to ground. The down-side is that feeding an input to the emitter requires a stronger drive voltage because the emitter input impedance is lower.

It is lower because the emitter fed input has to also "handle" collector currents as well as the little bit of emitter-to-base current normally needed for amplification.

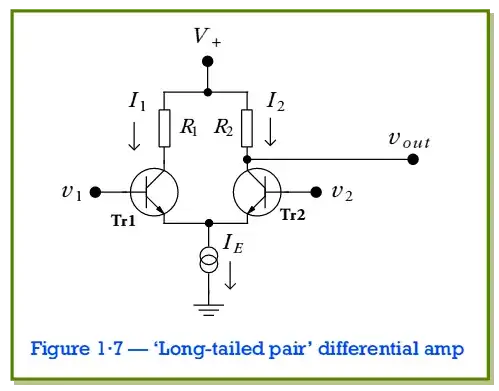

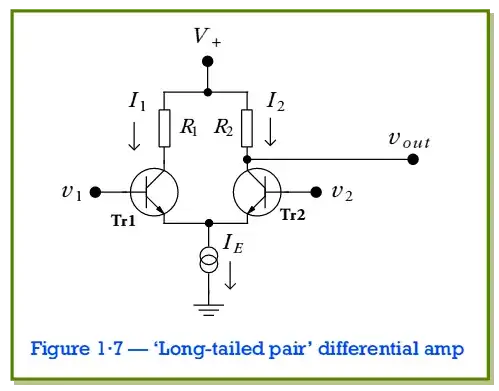

Consider also the differential amplifier: -

This is another circuit that uses the emitter as an input. On this occasion the input to the emitter comes from the emitter (outputting) of the other BJT. In fact, both emitters are simultaneously inputs and outputs.