A pretty thorough debunking of these ‘power saving’ devices can be found here: http://www.nlcpr.com/Deceptions1.php

Besides this, the box appears to be shoddily made and has no safety approvals. You should unplug it at once, it’s a hazard.

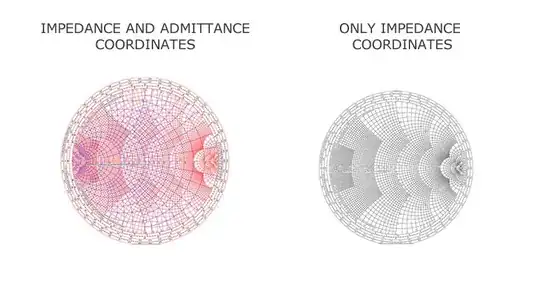

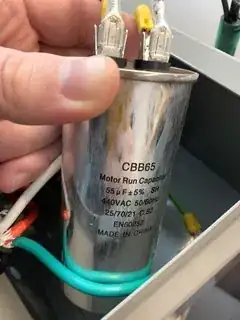

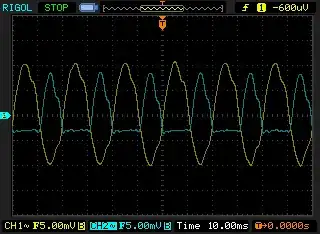

Like many scams, these boxes are based on a small kernel of truth. And that kernel is, applying a capacitor across the line compensates for inductive load influence on power factor. Properly sized (and connected, more below), a capacitor will reduce the dryer’s apparent power, which has a reactive component (the motor’s inductance).

Some background here: https://electricalacademia.com/basic-electrical/power-factor-correction/

So technically it could do something kind of useful, at least when the dryer is running and if its capacitor were connected correctly. Note the weasel-words ‘technically’ and ‘kind of’ and of course, 'if'. We’ll dig into this a bit.

It doesn’t do much of anything to protect against surges however, and being a capacitor, it’s vulnerable to them.

Why bother with a capacitor across the line at all? Non-ideal power factor adds additional load to the utility which must up-provision its infrastructure to handle apparent power, even though the reactive part of apparent power it delivers does no actual work at the consumer side. Utilities will charge large customers for this extra kVA capacity, often as a surcharge for less-than-ideal power factor.

So this power-factor correction technique, capacitors across the line, is used at big plants with lots of large motors. Unlike this dumb box, the plant’s capacitance is adjusted to achieve the best possible PF depending on the load at the time. Capacitors are switched in and out as needed to match the capacitor ‘lead’ with inductor ‘lag’ and thus cancel out the reactive power component seen by the utility.

More about that here: https://www.eaton.com/ecm/groups/public/@pub/@electrical/documents/content/sa02607001e.pdf

For home users, as it stands presently, this simple kind of power factor correction makes no economic sense. The reason is, home utility metering only measures real power regardless of power factor. You don’t get charged for less-than unity power factor like those big plants do.

Because home utility meter only tallies real, not reactive power, you will not save on your electric bill with this device.*

(*This could change down the line, as newer ‘smart’ meters can measure power factor. More here: How do residential analog and smart meters measure power?)

So, yeah, a scam.

That said, correcting power factor in the household is not nothing. There are regulatory initiatives to improve the power factor of appliances and electronics, as a means to make more efficient use of infrastructure.

IT gear is especially of concern these days, so you see power factor correction (PFC) being designed into power supplies above a certain wattage. Another major, emergent power factor pain point would be EV chargers, given their high power and long connection times, so these too benefit from PFC.

But your dryer? Not enough to bother. It’s kind of a small motor anyway (1/2 HP / 375W or so, compared to 5kW for the heating element.)

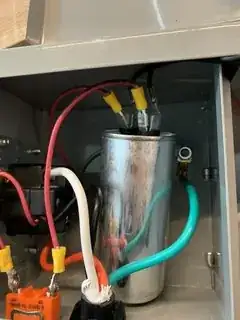

But the closer you look, the more dodgy this thing gets. The box wires the cap between L1 to L2 (black and red wires.) Dryers sold in 120V countries use a 'split-phase' arrangement, where the 120V motor is wired L1 or L2 to Neutral (white wire), while the heating element is wired between L1 and L2.

(Why? Gas and electric dryers sold in North America generally use the same 120V motor, saving cost and allowing them to be converted in the field. Gas dryers use a 120V plug, electric uses split-phase 240V.)

So the cap is not even connected correctly for a 120V dryer motor: any reactive cancelling it's doing is making its way all the way back to the opposite phase, to the utility pole, then back to neutral.

And even worse, as @Peter Green points out, having this capacitor across the line all the time, even when the dryer isn’t running, actually uses apparent power, working directly against the goal of optimizing household PF. Instead, it should be placed on the motor itself, sized appropriately to give the correct phase shift, and only switched in when the motor is on.

(Ed note: the box has a switch for the cap. You would need to remember to flip it on whenever you start the dryer, then flip it off again when the dryer stops. Not very practical.)

Finally, I see no UL approval on this thing. If it catches fire, and your insurance finds out about it they could use it as a basis to deny your claim.

Like I said, I’d disconnect it at once, and return it to Amazon if you can.

My best attempt at a schematic. Wire colors are correctly represented, blue is "white" and marked as such. Terminals are as marked on the receptacle.

My best attempt at a schematic. Wire colors are correctly represented, blue is "white" and marked as such. Terminals are as marked on the receptacle.