You can think of a battery as an electron pump, it chemically moves electrons from the positive terminal to the negative so as to maintain a certain 'electrical pressure' (That is what the early guys called potential difference in some old books, and it is not a bad model).

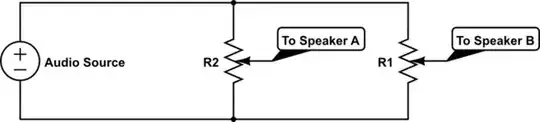

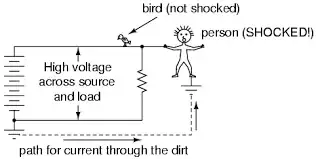

To actually make this thing do anything useful you need to provide a path for the electrons to flow that happens to use the moving electrons to do some kind of interesting task[1]. This might be heating a thin wire to make light, or powering some other electrochemical reaction to recharge another battery, or making a magnetic field in a motor or whatever. This path must clearly be a loop if you want the system to run more then very briefly (think nano seconds).

Note that at no point is there any mention of ground or such, all voltages are measured relative to some arbitrary point in your doings, and for that voltage to do anything useful there must be a loop for current to flow [2].

Ground is one of those really crap words that means at least 3 different things in a highly context dependent way, ignore for now.

[1] Electrons in a copper conductor at any sort of current you want to play with move on average really slowly, think less then a mm per second, but a wire is like a tube full of ball bearings, you push one in at one end, one pops out the other far faster then any ball actually moves down the tube.

[2] Yea, I know, flash memory gates, electrostatic lenses, laser printers, all sorts of slight exceptions, but roll with it for now.