A recent question on here asking about how to calculate the accuracy of a circuit got me thinking about calibration in general.

In particular, as EEs we routinely use volts and amperes as a unit and yet these are both rather vague and hard things to quantify.

It used to be that a volt was defined by a "standard cell" kept locked up in a vault somewhere, but that changed to using the "Josephson voltage standard" which is a complex system that uses a superconductive integrated circuit chip operating at 70–96 GHz to generate stable voltages that depend only on an applied frequency and fundamental constants.

The latter is not exactly something one could throw together in a basement, or even in the test engineering departments in most companies.

The Ampere is worse. It is defined in SI as "That constant current which, if maintained in two straight parallel conductors of infinite length, of negligible circular cross-section, and placed one metre apart in vacuum, would produce between these conductors a force equal to 2×10−7 newtons per metre of length."

I have NO IDEA how anyone could measure that.

The ohm used to be defined by a specific height and weight of mercury, but that was abandoned in favor of being a derived unit from 1V and 1A.

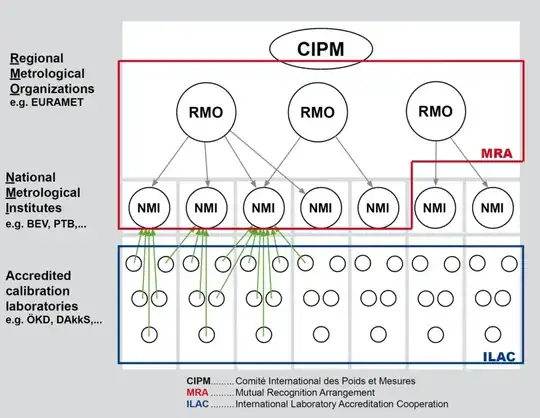

This all brings me to wonder how much of what we use is calibrated to someone else's meter. And how many of those meters are calibrated to yet someone else's... and on and on. Seems like one big house of cards.

Is there some sort of intermediate standard of measures or equipment you can buy to use as calibrated references for 1V, 1A, and 1R? (Obviously you only need any two of those.)

Bonus question: Is there some sort of certification sticker one should look for when buying a meter or other equipment that indicates it is indeed tested to the actual SI values vs tested against, say, a Fluke?